|

Of

these two temples the southerly one was excavated by Egyptologists

before the one in front of the Sphinx and so was regarded

for a time as the temple of the Sphinx - the discovery of

the other one, long buried under the ever-drifting sands,

established that the Sphinx's own temple was this one straight

in front of the eastward-facing monument. The two temples

are similar in size and both face east in a north-south alignment;

each has a pair of north and south entrances in their eastern

facades. They are both built with core blocks quarried on

site, around the body of the Sphinx: some of these core blocks

of the Sphinx temple are three times larger than the core

blocks of the Great Pyramid. Both temples were faced, inside

and out, with finely dressed granite from Aswan in the far

south of Egypt, and floored with alabaster.

The Sphinx temple is very ruined now, with little of its granite

facing left and little of its alabaster floor. Any inscriptions

it may once have carried, which might have told us much about

its purpose, are long gone. Only the eroded limestone core

of the structure remains, in part: enough to show that this

temple once boasted a central court, about 46 m by 23 m, open

to the sky and affording a good view of the Sphinx, and there

was an interior colonnade of rectangular pillars. Large recesses

in the inside eastern and western walls suggest the original

presence of cult statues, very possibly to do with the rising

and setting sun, but there is no trace of decorative detail.

There was no immediate access to the Sphinx from inside the

temple, whose west wall up to the height of 2.5 m was cut

into the living rock, and thereafter topped with limestone

blocks. It was necessary to go by passages to the north and

south of the temple to reach the Sphinx. There is evidence

that this temple of the Sphinx was never finished.

The interior of the other temple, to the south of the Sphinx

temple, is quite different in layout, though the same granite

casing of the limestone core blocks, rectangular style of

pillar, presence of statue niches, overall size and method

of construction mark both buildings as contemporary Old Kingdom

temples.

In the southerly temple, the remains of nine more or less

complete statues of a king named on them as Khafre were found.

Further fragments show that twenty-three statues of Khafre

once stood in this temple, which Egyptologists identify as

the valley temple of Khafre's pyramid complex: the temple

on the edge of the Giza escarpment to which his body was brought

by a canal from the river at the start of the process that

would end with his being sealed within his pyramid Up on the

plateau above. Even in this century, the river in flood has

occasionally come very close to the terrace of the temples

by the Sphinx - and the water-table is not far below ground.

|

|

The valley temple of Khafre lies at the end of a limestone

causeway that leads up the slope to a further temple at the

foot of his pyramid. The Greek writer Herodotus, who never mentions

the Sphinx as a feature on his visit to the pyramids (perhaps

it was all but obscured by sand in the fifth century BC), thought

the causeway of the Great Pyramid was as wonderful in its way

as the pyramids themselves. To judge by the causeways of slightly

later pyramids, these long ramps were covered over, with slits

in the roof to let in light, and possibly their walls even in

the time of Khufu and Khafre carried sculpted and painted scenes

on them, in contrast to the lack of decoration in the Giza pyramids

themselves.

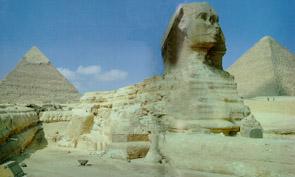

The

Great Sphinx in modern times.

|

The Khafre causeway was equipped with drainage channels which

are interesting because they indicate that rainwater run-off

was an essential provision of the pyramid complex. We are accustomed

to think of Egypt as a very dry place but even nowadays, rain

can sometimes cause considerable damage in a context where it

is not routinely expected. Evidently the monuments of the Giza

necropolis needed precautions against rain. On the north side

of the Khafre causeway, there is a ditch (2 m wide and 1.5 m

deep) that forms a demarcation line between the pyramid complexes

of Khufu and Khafre. This rock-cut ditch was large enough to

channel a great deal of rainwater when heavy rains occurred.

It is cut into by the corner of the Sphinx enclosure, and -

were it not blocked at this point with pieces of granite - would

allow water to pour in quantity into the basin out of which

the Sphinx body was carved. These circumstances strongly suggest

that the Sphinx enclosure and the Sphinx itself were created

after the demarcation of the complexes of Khufu and Khafre and

after the construction of Khafre's causeway.

There are some tombs cut into the south-facing edge of the

wider Sphinx enclosure to the north that belong to the same

Dynasty IV as Khufu and Khafre, showing that the enclosure was

not made after their time. Between them, the blocked ditch and

the tombs indicate a narrow hand of time in which the Sphinx

enclosure, and by strong implication the Sphinx itself, could

have been carved. It means that the Sphinx most likely dates

to a time no later than a couple of reigns after Khafre and

no earlier than his reign.

|