|

The

rock was of poor quality from the start, with fissures along

joint lines going back to the formation of the limestone millions

of years ago. There is a particularly large fissure across the

haunches - filled with cement - which also shows up in the walls

of the enclosure in which the Sphinx sits.

So severe is the erosion of the body of the Sphinx that, what

may have been an entire statue or attached column standing proud

from the breast of the beast, has been reduced to a formless

line of protuberances on the front of the monument between the

forelegs. It is plain that extensive repairs have been made

to the front paws of the Sphinx and in many other places over

the body.

Some of these repairs go back to the New Kingdom of around 1400

BC(the time when King Tuthmosis IV set up his stela between

the paws), and there is reason to believe that parts of the

Sphinx must have been built on the carved body, arising out

of necessity of the poor state of the rock. It is even possible

that the body of the Sphinx was entirely plastered over at some

stage.

Below the neck, the Sphinx has the body of a lion, with paws,

claws and tail (curled round the right haunch), sitting on the

bedrock of the rocky enclosure out of which the monument has

been carved. The enclosure has taller walls to the west and

south of the monument, in keeping with the present lie of the

land: it is generally thought that quarrying around the original

knoll (for pyramid blocks or blocks with which to build temples

associated with the necropolis complex) revealed the too-poor

quality of the rock for construction purposes at this point;

whereupon some visionary individual conceived the plan of turning

what was left of the knoll into the Sphinx; but, of course,

the Sphinx may equally well have been planned from the start

for this location. The walls of the Sphinx enclosure are of

the same characteristics as the strata of the Sphinx body and

exhibit similar states of erosion.

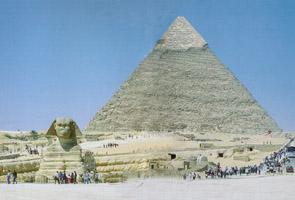

The Sphinx

lying in its enclosure,

mobbed by the tourists of today. |

There are three passages into or under the Sphinx, two of

them of obscure origin. The one of known cause is a short

dead-end shaft behind the head drilled in the nineteenth century.

No other tunnels or chambers in or under the Sphinx are known

to exist. A number of small holes in the Sphinx body may relate

to scaffolding at the time of carving.

The Great Sphinx is huge. The length of the body is more than

74 m; its height from the floor of the enclosure to the top

of the head some 20 m. The extreme width of the face reaches

over 4 m, the mouth being 2 m wide; the nose would have been

more than 1.5 m

|

|

long,while the ears are well over 1 m high. Not even the giant

New Kingdom statues of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel, sculpted thirteen

hundred years after the Sphinx, at 20m high with faces about

3 m wide exceed the Old Kingdom monument.

The wrecked statue of Ramesses II that inspired Shelley's poem

about Ozymandias was evidently about 18 m high. Similarly, the

huge seated statues of Amenophis III called the 'Colossi of

Memnon' are no taller than the Sphinx and, again, not so bulky

- though they were entirely made out of single blocks and transported

to their location. The statue of Zeus at Olympia, made by Phidias

in the mid-fifth century BC, was neither quite so tall nor made

out of one piece of material; the Colossus of Rhodes was reputedly

half as tall again as the Sphinx, but put together out of bronze

castings.

Mount Rushmore makes the closest modern time comparison with

the Sphinx, with its faces at 18m in height. The Statue of Liberty

tops them all at 92 m, but is made out of copper sheets hammered

together, over a framework of steel.

This was, as far as is known, the first of the Egyptian sphinxes:

the rules of proportion commonly employed on later and smaller

examples may not yet have been formulated at the time of the

carving of the Great Sphinx of Giza. In any case, the sphinx

pattern was always a flexible formula, to an unusual degree

in the context of Egyptian artistic conservatism. Then again,

the Sphinx may have been sculpted to look its best when seen

from fairly close by and more or less from the front. It is

possible that there was simply insufficient good rock to make

the head bigger, where fine detail was required.

The Sphinx sits in an enclosure formed by the removal of limestone

from around its body. This enclosure is deepest immediately

around the body, with a shelf at the rear of the monument where

it was left unfinished, and a shallower extension to the north

where important archaeological finds have been made. Without

the excavation around it, the Sphinx would at best have no carved

body below the level of the uppermost part of its hack: it would

look as it did when the sands buried it almost up to its neck

in the nineteenth century.

The good, hard limestone that lay around the Sphinx's head was

probably all quarried for blocks to build the pyramids. It was

perhaps the removal of this limestone, leaving at some stage

a suggestive lump of remaining rock (together with the discovery

of poor rock beneath), that inspired someone to create the Sphinx.

The limestone removed to shape the body of the beast was evidently

used to build the two temples to the east of the Sphinx, on

a terrace lower than the floor of the Sphinx enclosure - one

almost directly in front of the paws, the other to the south

of the first one.

The core blocks of these two temples are of the same poor quality

and more easily eroded limestone as the body of the Sphinx.

Thus these temples can be regarded as contemporary with the

carving of the monument.

|