|

The

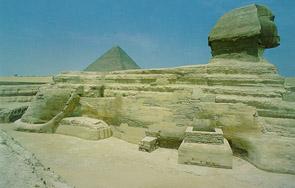

Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza has a rival for size and grandeur

very close at hand. Standing next to it is the pyramid of

Khufu's successor Khafre, which from many angles looks bigger,

having been built on slightly higher ground. Indeed, the ancient

Egyptians called the Pyramid of Khafre 'The Great Pyramid'

and that of Khufu 'The Pyramid which is the Place of Sunrise

and Sunset'. Although a difference of only a few metres in

height, The Great Pyramid is actually higher, has a shallower

angle of incline than Khafre and encloses a bigger volume.

The Sphinx on the otherhand, stands alone, with no rivals

either on site or elsewhere among all the sphinxes of Egypt.

Truly, this is the Great Sphinx, as well as very likely being

the first of the breed. The Great Sphinx started off as a

knoll of rock (quarried in the course of pyramid building)

at the bottom of the Giza Plateau towards the valley of the

Nile.

The later sphinxes of Egypt were often installed as pairs

to guard entrances to significant places, but the Great Sphinx

of Giza is a one-off. And perhaps the original meaning of

the Great Sphinx was too particular to be shared with another

of its kind.

The damaged face of the Sphinx,

smiling inscrutable smile |

The Sphinx is carved out of the living rock, though parts

of it have been repaired with blocks of stone. It is immediately

apparent that the rock strata of which the Sphinx is made,

varies from a hard grey to a soft yellowish limestone. The

head is made of hard limestone of the same sort as was quarried

around the pyramids. The body on the other hand, is made of

poorly consolidated and therefore readily eroded limestone.

The rock improves again at the base of the monument, with

a return to harder (but brittle) reef-formed limestone that

has allowed some carved details of the beast to remain visible

after at least four-and-a-half thousand years of natural and

human attrition.

In keeping with the whole Giza Plateau, these strata within

the Sphinx run from east to west, in other words from the

breast to the hindquarters, and north to south. The Sphinx

faces due east, with the same great precision of orientation

as is seen in the disposition of the Giza pyramids.

The

heavily eroded Sphinx. |

|

|

The

monument was made from the start to point directly to sunrise.

Interestingly, the face, excluding the ears is a little awry

in relation to the head as a whole: the left eye is slightly

higher than the right, the mouth off-centre, and the entire

face slightly tilted back.

Despite

the overall better quality stone of the head, the face - as

is immediately apparent - is badly damaged, and not just by

natural erosion. The nose is missing altogether and the eyes

and the areas around them are seriously altered from their

original state, as is the upper lip. Napoleon's artillerymen

have been blamed for using the face of the Sphinx for target

practice.

Fragments

of the Sphinx beard:

casts in the Cairo Museum |

The alteration of the face has brought an insinuation of mood

to the features, which change with the different lights (sometimes

into a knowing smile). This has to be borne in mind when any

attempt is made to compare the face of the Sphinx with the

sculptures of various fourth Dynasty kings.

The head and face of the Sphinx certainly belong to the Old

Kingdom, particularly the fourth Dynasty. The style of the

headdress (known as the 'nemes' head-cloth), with its fold

over the top of the head and its triangular planes behind

the ears, the presence of the royal 'uraeus' cobra on the

brow, the treatment of the eyes and lips all speak of that

historical period.

The sculptures of kings Djedefre, Khafre and Menkaure all

show the same configuration that we see on the Sphinx. Originally,

the Sphinx had a plaited beard seen on many Egyptian statues.

Pieces of the Sphinx's massive beard found during various

excavations adorn the British Museum in London and the Cairo

Museum. The beard was supported by a stone plate to the breast,

parts of which have also been found.

A

hole in the top of the head that is now filled in, indicates

that there was once a head decoration. Depictions of the Sphinx

show a crown or plumes on the top of the head, but these were

not necessarily part of the original design. The top of the

head is flatter, however, than later Egyptian sphinxes. Serious

natural erosion of the body of the Sphinx begins below the

head.

In the 1920s it was considered necessary to support the

head with cement approximations of the absent parts of the

head-dress, and it is these extensions that chiefly account

for the altered appearance of the Sphinx's head in recent

times, when compared with old photographs and drawings.

The

Sphinx temple in front of the Sphinx. |

Erosion below the neck does not look like scouring by wind-blown

sand. In fact, so poor is the rock of the bulk of the body

that it must have been deteriorating since the day it was

carved. And it continues to erode before our very eyes, with

spalls of limestone falling off the body of the Sphinx in

the heat of every day.

|