Because

it relates the creation of the entire world, the creation

myth (also called cosmogony) is generally regarded as

the most important of all the myths in a culture. The

creation of the world is the theme of several ancient

Egyptian myths, yet four of them take precedent over the

others: the creation myths of the cities of Heliopolis,

Hermopolis, Memphis and Thebes.

The Heliopolitan Cosmogony

Allusions to the Heliopolitan creation myth have survived

the passage of ages in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts,

the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom, the Book of the

Dead (New Kingdom) and Papyrus Bremner-Rhind. None of

these textual sources actually have a full narrative of

the creation of the world as established by the priests

of Heliopolis; however, the various references in each

text allow the reconstruction of the crucial moments of

the creation story.

The ancient Egyptians did not perceive the coming into

being of the world as a creation ex nihilo (out of nothing).

Instead, at the very beginning there was a chaotic primordial

watery body called Nun. Nun, even though it was 'pre-existence'

and never really part of the real world, contained all

the elements -- albeit inactive -- necessary for the creation.

Within this pre-existing aquatic milieu, the god Atum

willed himself into existence and emerged from the watery

chaos. Henceforth, Atum was known as 'The One who Created

Himself.' Having nowhere to stand Atum then created the

first hill, which also emerged from Nun. The imagery of

the first hill emerging from the waters of the primordial

ocean would have been familiar to any ancient Egyptian.

Every year, after the flooding of the Nile River, the

submerged land suddenly re-appeared like little sand hills

as the river receded and the water level lowered. The

Egyptians believed that the annual flood was a repetition

of the time of creation, the First Time.

Atum's next task was to create other gods. However, standing

alone on the first hill, he had to perform this feat without

a mate. Utterance 527 of the Pyramid Texts and Papyrus

Bremner-Rhind both state that Atum grabbed his phallus

in his hand and masturbated in Heliopolis. The twins Shu

(male) and Tefnut (female) were born as a result of his

orgasm. It is generally said that Shu was spat out and

Tefnut vomited from Atum's body.

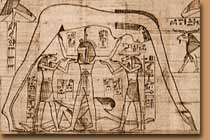

Shu, the god of air, and his sister-wife Tefnut, the goddess

of moisture, coupled and continued the works of creation

by begetting the gods Geb and Nut, two very important

deities. The ancient Egyptians viewed the earth as a male

entity, the god Geb, and the sky as female, the goddess

Nut. After the Earth and Sky gave birth to four children

(Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys), Atum ordered that they

be disentangled from their loving embrace and separated

from one another by Shu, the air (see image below).

|

|

| |

These

nine gods (Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris,

Isis, Seth and Nephthys) are called the Ennead

of Heliopolis. The first five deities each

represent an element of nature: the sun, air,

moisture, earth and sky. The four others,

together with Geb and Nut, play the leading

roles in the myth of kingship, which will

be presented in a later lesson. |

|

|

The Hermopolitan Cosmogony

The Hermopolitan creation myth is unlike the other creation

stories. It distinctive trait resides in the fact that

its formulators believed that the entities who set the

creation of the world in motion lived in a Golden Age

before the First Time. They believed it actually pre-dated

the Ennead of Heliopolis.

In the Hermopolitan cosmogony, the chaotic primordial

watery body was described as more complex than Nun, as

seen in the Heliopolitan creation myth. Nun represented

only part of the primordial slime. Actually, eight entities,

who were divided in four couples, composed the primordial

ocean. Male deities were depicted as frogs and the goddesses

as snakes, and each pair represented a concept describing

the pre-world :

Nun (m) and Naunet (f) = primeval waters

Heh (m) and Hauhet (f) = eternity

Kek (m) and Kauket (f) = darkness

Amun (m) and Amaunet (f) = invisibility

Eventually, the Eight (also known as the Ogdoad) interacted

explosively and the blast of their powers resulted in

the bursting forth of the first hill from the watery chaos.

The primeval hill is often referred to as the Isle of

Flame because the creator god Ra (the sun god) was born

on it and the universe witnessed its first sunrise.

The Ogdoad's part in the story is most important in the

fact that in Hermopolis they were believed to have created

the sun god. However, after creation is set in motion,

the Eight -- with the exception of Amun -- retire from

the narrative and go live in the underworld where their

power causes the Nile to flow and the sun to rise each

day. As for Amun, he left Hermopolis and took residence

in Thebes, where he plays the leading role in the Theban

cosmogony.

The complexity of the Hermopolitan cosmogony is partly

based on the scantiness of textual evidence recounting

the creation myth. Most of the evidence for this narrative

comes from Theban monuments rather than Hermopolis itself.

Indeed, the destruction (or possibly 'unexcavation') of

the monuments of El-Ashmunein (the modern name for Hermopolis)

leave little for the understanding of the creation of

the world by the Ogdoad and the sun god. An additional

reason for the intricacy of the myth resides in the multiple

versions of the story. |

|

A version of the Hermopolitan cosmogony involves

a celestial goose. This goose, commonly known as

the Great Cackler because it was the first creature

to break the silence, laid an egg on the primordial

hill. The sun god Ra, who thereafter continued the

creation process, broke free from this egg. In another

slightly different (and later) version, it is an

ibis that lays the egg on the island. This later

version was adapted to the story of the Ogdoad because

the priests of Hermopolis wanted to promote their

local god Thoth (whom the Greeks knew as Hermes,

hence the name Hermopolis). An association with

the Ogdoad would have given Thoth more power and

seniority over other popular gods.

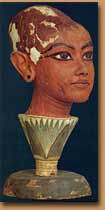

The most poetic version of the Hermopolitan myth

reverts to creation coming out of the chaotic primeval

ocean. Indeed, in this rendition of the story, it

is a lotus flower that is said to emerge from the

waters. The petals of the lotus flower unfolded

and sitting on the calix (the centre / heart of

the flower) was a divine child, the god Ra. A remarkable

sculpture found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun

shows the head of the young king emerging from a

lotus flower, the petals fanning out around his

neck -- an image that depicts the young king with

the powers of the creator god Ra (see image left).

|

|

In

a variation of the lotus flower theme, it is a scarab

beetle that emerges from the petals of the flower and

who then turns himself into a little boy who weeps. The

scarab beetle is an important symbol of the sun god Ra

and this will be explored in later lessons. |

| End

of Part 1 |

|