|

When

studying the religion of the ancient Egyptians, we are

confronted with a multitude of gods, represented in

a variety of ways. In order to understand their mythology,

we must first attempt to understand how the ancient

Egyptians viewed their gods.

The Egyptians' concept of "god" is not easy

to define. There were many gods and goddesses, many

of them representing different aspects of life and nature.

Hence Osiris was the god of the dead; Hathor was the

goddess of love, procreation, wine and music; Isis was

the goddess of motherhood, and so on. However, not all

gods represented exclusively good aspects of life. Sekhmet,

for instance, represented vengeance and disease whereas

Seth represented the desert and chaos. Nevertheless,

this does not mean that Sekhmet or Seth were viewed

solely as bad gods: Seth plays an important part in

the protection of the deceased solar god during his

journey through the underworld every night.

Despite the multitude of gods, there has been some debate

whether or not these seemingly different gods could

represent different aspects of the same god. Many gods

were associated with the solar-god Re, thus turning

them into solar-deities as well and making them share

some of the same characteristics. As Egyptian religion

evolved, more and more gods were assimilated into each

other, while still retaining their individuality. Hence

Khonsu and Thot, both lunar deities, could be assimilated

into Khonsu-Thot, a lunar god with both Khonsu's and

Thot's characteristics while both Khonsu and Thot continued

to exist individually. Such "syncretism" makes

it difficult to understand the individual characteristics

of the different gods.

Gods could also share some characteristics without being

explicitly associated with each other. Several important

cities would, for instance, promote their own, local

god as the creator of the world: Atum in Heliopolis,

Ptah in Memphis, Amun in Thebes, … were all credited

with having created the world and each of them had their

own creation myths.

Basically there were male and female deities. Several

deities, however, could be considered as having both

genders. Shu, the god of the air, for instance, can

sometimes be represented as a man with breasts, whereas

the goddess Neith is said to be 2/3 male and 1/3 female

but she is always represented as female. Gods with bi-sexual

traits were often creator-gods who needed both the male

and the female aspects to be able to create the world.

The ancient Egyptians often grouped their gods. The

smallest group consisted of two gods, generally composed

of a male and a female deity.

More

typical were triads, consisting of 3 gods, usually in

a father-mother-son relationship. The most popular triads

were Osiris-Isis-Horus and Amun-Mut-Khonsu.

An

Ogdoad grouped 8 gods, 4 times a couple, each couple

representing the male and female aspects of the elements

that were present before creation. Unlike other groupings,

the Ogdoad consisted of specific gods, which will be

discussed in the upcoming article on Creation Myths.

An

Ennead normally consisted of 9 gods, but as 9 is 3 times

3 and 3 was viewed as "plural", an Ennead

could also be viewed as a gathering of many gods. The

most important Ennead was located at Heliopolis, to

the northeast of Memphis. Several cities had their own

versions of the Ennead of Heliopolis, some headed by

the principal god of that city, others just "copies"

of it, to which some local gods were added.

The

reasons why some gods were grouped together are not

always clear. Sometimes, gods in a group have similar

or complementing characteristics, as was the case with

the Ennead of Heliopolis, for instance where the first

5 gods represented an element of nature (sun, air, moisture,

sky and earth). The relationship between Ptah, Sekhmet

and Nefertem, the members of the Memphite triad, however,

is not really clear.

One of the most striking features of ancient Egyptian

gods is the way they were represented. They could be

represented as humans, humans with the heads or other

features of animals, as complete animals, as plants

or even as objects. Amun, for instance, is usually shown

as a man wearing a crown with high feathers, but occasionally

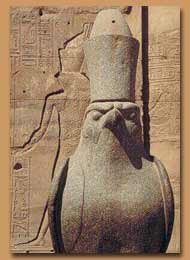

is depicted as a man with the head of a ram. Horus,

on the other hand, can be represented as a human child,

as a man with the head of a falcon or as a falcon. One

form of Horus, Horus of Edfu, is often represented as

a winged solar disk.

Even more fantastic are gods like Tutu, a winged lion

with the head of a man, a crocodile extending from his

chest and a snake-shaped tail.

|

|

|

"Two

times Horus: the statue in the foreground represents

him as a falcon, the relief behind the statue

shows him as a man with the head of a falcon"

|

|

Strange as such representations might seem at first, they

are more indicative of the nature of a god rather than

what he looked like. Hence Horus was associated with a

falcon, because primarily, he was a god of the heavens.

He was also a powerful and strong god, so he wasn't associated

with just about any bird, but with the most dangerous

bird of prey known to the Egyptians.

Anubis was represented as a man with a dog's head, or

as a dog, because dogs were associated with places of

burial. He was black because black was the colour of death.

Hathor, usually represented as a female, is sometimes

represented as a woman with cow's ears, as a woman with

a cow's head or as a cow, because she was the goddess

of procreation, fertility and motherhood.

Because we do not always know what characteristics the

Egyptians associated with animals, we can not always explain

why a particular deity was associated with a particular

animal and represented as such. We do not know, for instance,

why Thot, the god of wisdom and writing, was associated

with an ibis. |