| Development

of Ancient Egyptian Art |

Historical

Periods

Indeed,

the uniformity of Egyptian art is quite remarkable. Nevertheless,

each historical period has distinctive traits, whether it

be fashion, hairstyle, the prominence of a specific deity,

innovation, or foreign influence. Art of the major historical

periods is briefly presented here, giving a glimpse into the

rich artistic expressions, creativity and cleverness of the

ancient Egyptians.

Predynastic

Period

Egyptian art of this period flourished in independent cultural

centres in both Upper and Lower Egypt at sites such as Badari,

Naqada, Merimde, and the Fayoum. The artistic expression is

quite primitive - as if it were drawn by a child. Stick men

herding bovines or hunting gazelles. Stick sailors on boats

with numerous oars and a prominent deck cabin. Females standing

with hands above their heads. Yet, the exact meaning of these

simple drawings somewhat eludes us. The composition of the

scenes does not appear to follow strict rules, with an exception

or two. Boats were depicted amongst groups of people hunting,

wrestling with one another or with wild beasts. Were the Egyptians

depicting normal, every day life, a major event, or a funerary

procession on the Nile? Who are the female figures with their

arms raised above their heads?

|

Female Figurines from the Predynastic Period now found

at the Royal Ontario Museum

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

Along

with drawings painted on tomb walls (such as Tomb 100 at Hierakonpolis)

or ceramic vessels, the ancient Egyptians carved exquisite

ivory combs with zoomorphic handles, ivory anthropomorphic

figurines, and stone palettes. They also made ceramic figurines

and magnificent stone vessels. The zoomorphic motifs, either

painted or sculpted, are comprised of an interesting variety

of animals, reptiles, and birds that are not always equated

with Egypt: giraffes, hippos, ostriches, gazelles and numerous

horned animals, crocodiles, flamingos, fish, iguanas, turtles,

lions, ibis, and dogs. Statuary is developed extremely slowly

and is non-existent at this period.

By late Predynastic period, ancient Egyptian art had incredibly

matured and can be considered as a transition phase into the

Archaic period. Numerous palettes carved in greywacke, a hard

dark grey stone, and decorated with animals, emblems of towns

and forts, as well as fighting scenes seem to allude to a

period of confrontation between groups of people. Possibly

the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Archaic

or Early Dynastic Period

The Archaic period represents the formative stage of the ancient

Egyptian civilisation, as we know it. After the unification

of the Two Lands under the rule of a single king, Egyptian

art was completely transformed. The chaotic aspect of Predynastic

art has been abandoned and replaced by structured compositions.

Artistic conventions that were to control Egyptian art for

the three millennia to come were adopted during this epoch.

The Narmer palette, the most beautifully preserved monument

of the Archaic period, represents King Narmer (Dynasty 0)

grabbing a foe by the top knot and about to smite him with

his mace head. This prototypical representation of the king

would become part of royal iconography until the death of

ancient Egyptian civilisation. It symbolised superiority of

the Egyptian king, who held a divine office and was the beholder

of Maat, cosmic harmony.

|

Facsimile of the Narmer Palette from then Dynasty 0

found at the Royal Ontario Museum

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

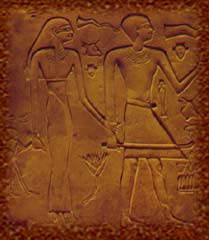

Archaic

art that has survived is comprised mostly of statuettes of

the king wrapped up in a cloak, stelae with the king's name

in a serekh, engravings of the king smiting an enemy as well

as a few statuettes and stelae of nobles and priests.

Old

Kingdom

The epoch also known as the 'age of the pyramids' was an era

of great architectural achievement and unsurpassed aestheticism.

Statuary reached new heights - literally - as artists produced

life size or almost life size statues. Additionally, exquisite

details such as inlaid eyes, together with richly coloured

paint contributed to their beauty and their lifelike impression.

These 'living images' were nevertheless not portraits in the

true sense of the modern word even though artists paid a certain

attention to facial features. These statues, although elegant

and polished, were not intended for public viewing. Private

statues of individuals were destined for tombs and were accessible

only to priests who would bring for them daily offerings and

perform rituals in order to sustain the deceased in the Afterlife.

Royal statues must be considered as an entirely different

category, not only because of their superior craftsmanship,

also because of their intended use. Statues of kings had a

political goal: asseverate the status of the ruler within

society.

Paintings and reliefs, which decorated private tombs with

scenes of every day life, the deceased performing his tasks

and his daily job, family activities, such as hunting and

fowling scenes, as well as funerary and religious scenes,

attained the same quality of execution as statuary. These

scenes ensured the survival (and the pleasure) of the deceased

in the Afterlife; should the priest responsible for the upkeep

of the tomb and the bringing of offerings fail his duties,

the depiction of the deceased sitting at a table garnished

with food and drink would, with a little magic of course,

suffice to nourish him or her.

Royal reliefs and paintings found in temples serve, once again,

a political agenda. Pictures of the king striding forward

as if running were representations of Heb Sed festival (the

30 Year Jubilee of the king's reign) during which the king

ran laps in order to prove to his people that he was strong

and fit to rule. The king could also have been represented

bow and arrows in hand, hunting wild beasts in the desert;

a scene that intimated his skill as a provider for his people,

that demonstrated him as a fearless leader ready to brave

wild beasts to protect his country, but mostly as a king who

sees that Maat, the goddess and the concept of cosmic harmony,

reigns in the Two Lands. There is also the ever-famous smiting

scene where, like on the Narmer palette, the king shows his

superiority over a foe.

|

|

Old

Kingdom statues, as well as paintings and reliefs, depicted

humans as eternally young and beautiful, staring straight

ahead, lost in contemplation. Men were represented at the

height of their physical fitness: large shoulders, flat abdomen,

muscular biceps and legs. They sported short kilts that showed

off the muscles in their thighs and calves. Women were svelte

and gracious, and their narrow hips, flat belly and full firm

breasts were enhanced by the extremely tight sheet dresses

they donned. Most wore wigs, as indicated by a second hairline

on their forehead.

|

Funerary Statue of Kapuptah and his wife Ipep from the

5th Dynasty found at the Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

There

is an inherent nobility exuding from Old Kingdom statuary

and reliefs that is somehow absent in the later periods, even

during the New Kingdom.

First

Intermediate Period

The Old Kingdom ended in disunity and chaos; the centralised

power of the king crumbled, a severe drought swept the country,

and a civil war broke out. Needless to say, art suffered immensely.

Royal workshops being closed, artists had no rigorous training

and could only copy Old Kingdom reliefs, paintings and sculptures

to the best of their abilities. Some artists had talents,

others did not. Human figures with disproportionately long

limbs and awkward silhouettes were depicted in curiously rendered

actions and movements. Yet, the art of the First Intermediate

Period has a certain naive charm.

|

Funerary Stelae of Neferher and his wife Senet from

the First Intermediate Period found at the Royal Ontario

Museum

|

Credits: Caroline Rocheleau |

Middle

Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom, referred to as the golden age of ancient

Egyptian literature, generally is forgotten when discussing

Egyptian art. Yet, even though fewer monuments and masterpieces

have survived the passing of time, Middle Kingdom art was

perceived as "classical" art by later generations of Pharaohs.

Artists of the Late Period were so inspired by the Middle

Kingdom that they replicated sculptures and paintings with

such great care that even Egyptologists have difficulty ascribing

an art piece to one of the two epochs!

Although art appears quite eclectic as a result of different

styles adopted during the reign of each king, the royal artists

nonetheless achieved great technical quality in their work

and, more importantly, intense degrees of individualism and

realism. The Egyptians of the Middle Kingdom performed the

same activities that Old Kingdom people did and they painted

those in their tombs. Middle Kingdom kings built impressive

fortresses in Nubia and made sure that the Nubians were aware

of their power by having stelae carved with an image of them

smiting a Nubian enemy. However, the major differences reside

in the different quality of execution, the new expressive

and realistic qualities of the art, and the fashion of the

time.

During the Eleventh Dynasty, art resembled greatly that of

the Old Kingdom, both in artistic rendition and clothing style,

even though the quality is not as excellent. Distinct changes

occurred after the reign of King Amenemhat the First, the

first king of the Twelfth Dynasty. Artistic expression revealed

an increasing tendency towards a more expressive style, with

greater degree of realism. The most striking examples of individualism

date to the reign of King Senwosret the Third, the apex of

Egyptian expressionism, if one can call it that. A magnificent

granite statue in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo presents the

king in the most realistic manner - previously unseen and

never later equalled. Senwosret's surprising melancholic facial

expression is enhanced by the small sunken eyes, sleepy eyelids,

emphasised eyebrow ridges, bags under the eyes, and a downturn

smile. Despite this fatigued expression, ancient Egyptian

texts describe Senwosret the Third as a self-conscious, determined,

and ruthless king.

Also during the Twelfth Dynasty new fashion styles that help

differentiate art from previous and later periods appeared.

Women now wore their hair / wig in the 'Hathor' style: medium

length hair brought over the shoulders and curled at the ends.

Like Old Kingdom women, they wore tight dresses. Men wore

shoulder length wigs that were very thick at the ends quite

different from the short, thin hair of many Old Kingdom men.

They also wore a much longer kilt (mid-calf) that very often

was tied underneath the arms, a bit like a wrap around dress.

Second

Intermediate Period

Little is known of the Second Intermediate Period, a time

when Egypt was ruled by foreign kings, the Hyksos. Much as

yet to come to light before the epoch can truly be understood.

Ongoing excavations at the site of Avaris (the Hyksos capital

city situated in the north-east Delta) have revealed the most

surprising fragments of painted plaster that resemble Minoan

frescoes of the Palace of Knossos in Crete.

New

Kingdom

The New Kingdom was an age of international relations during

which Egypt was a dominant power in the Near East. The Hyksos

invasion had shown the Egyptians their own weakness and had

scarred the common Egyptian psyche. Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs

(as they can now be called) extended their territory beyond

the borders of Egypt, creating buffer zones to protect their

country from further invasions. Lands as far south as modern

day Sudan and as north as modern day Syria were under Egyptian

domination.

For

the first time in its history, Egypt had an actual standing

army rather than conscripts and a handful of mercenaries.

This new military aspect of ancient Egyptian society had an

interesting impact on art. Temples were decorated with kings'

military expeditions and exploits, and this time they were

doing more than smiting an enemy with a mace head. New Kingdom

pharaohs were represented standing in their chariot, reins

strapped around the waist, shooting arrows and trampling enemies.

Even thought the scene was different, the propagandist message

remained unchanged.

(Caroline

Rocheleau)

|

|